Once again, I am not a veterinarian and do not claim to know everything about horses. I just wanted to put these together to be fun and informative reads for those who love horses and learning about them! So with that being said, let's get to it.

Hind Legs:

Although I focused on how important the forelegs are, that does not mean that the hind legs aren't important. A horse's impulsion comes from their hind end, therefore a weak hind end is never a good thing.

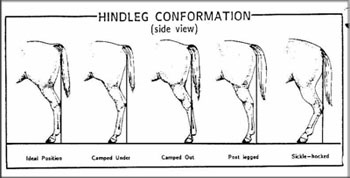

Figure 1

Figure 2

I

included two figures that help to illustrate different conformation

faults in the hind, and they both include an "ideal" example as well.

In Figure 1, the "plumb line" is dropped from the point of the buttock

straight down. An ideal position would be to have the point of the hock

to the end of the cannon follow a straight line down. Variations of

this will cause varying soundness issues - some being worse than others.

(I will discuss lamenesses in another post... Stay tuned)

Horses

that are "camped out" typically have upright rear pasterns and have

decreased stride efficiency. It will be more difficult for the horse to

engage the hindend, and therefore difficult for the horse to do upper

level disciplines. Camped out horses may also be prone to quarter cracks

and arthritis.

A

horse that is "post legged" has hind legs which are too 'straight'.

Straight legs will also cause the horse to have a difficult time getting

it's hind legs underneath itself, and the horse will generally move

with more concussion to it's hind legs - making it more prone to quarter

cracks and arthritis. Being straight through the stifle causes tighter

ligaments across the patella (joint in the stifle), increasing the risk

for upward fixation of the stifle joint and arthritis in the stifle. A

post legged horse will also have increased tension in the joint capsule

and cartilage of the hock. This can predispose the horse to several

problems - including bog spavin, bone spavin, and thoroghpin. (To be

discussed in a different post)

Horses

who are bow-legged in the hind move in a manner that puts stress on the

lateral sides of their legs/hooves. This predisposes the horse for

lameness problems like bog/bone spavin and thoroughpin as well. In

addition, the circular motion in which the horse must move it's hind

legs can also lead to arthritis, quarter cracks, etc.

So, with what I said about there being an "ideal" position, it can vary based off of the breed and what you are wanting the horse to excel at.

Typically, if you are looking for a "riding horse", no matter what the discipline, you would look for something closer to the "ideal" positions illustrated in Figure 1 and 2.

As you can see, any deviation from what is "ideal" will come with some sort of repercussion. (Arthritis being a big one)

Croups

The croup is from the lumbosacral joint to the tail. Horses do well with different angles of croups. Usually, it is desirable for a horse to have a croup that is as high as it's withers. However, there are breed deviations. In addition, breeds such as the Quarter Horse tend to be bred for a steep croup and breeds such as the Arabian or Saddlebred typically have flatter croups. A steep croup (also sometimes known as a "goose rump") is often linked to a shorter stride - but a steep croup and long hip is usually preferred in Quarter Horses. A flat croup encourages a long stride with not very much suspension. This is particularly handy for a horse such as the Arabian which was originally bred for its endurance - they move pretty fast without expending a bunch of energy.

A "goose rumped" horse

A flat crouped horse

*Horses

with flatter croups are usually more apt to having high-set tails. This

usually doesn't have any advantage or disadvantage, and just comes down

to personal preference.

Fun

Fact: A myth about how the Arabian horse breed was created states that

the Prophet Muhammad chose his foundation mares by selecting them for

courage and loyalty. The myth states that after a long journey through

the desert, he set his horses (who were all immensely thirsty) loose to

drink out of an oasis, and just before they reached it - he called them

back. Out of his herd, 5 mares turned on their heels and came back to

him without a drink of water. These mares became the 5 foundation mares

of the Arabian breed... Or so the myth says!

That's

all for this post, I have to get to studying for my classes. I hope you

enjoyed and found it helpful! If you have anything you would like me to

write about in my next post that is horse-related please comment below

or on my instagram! (@laurenanddante)

xo